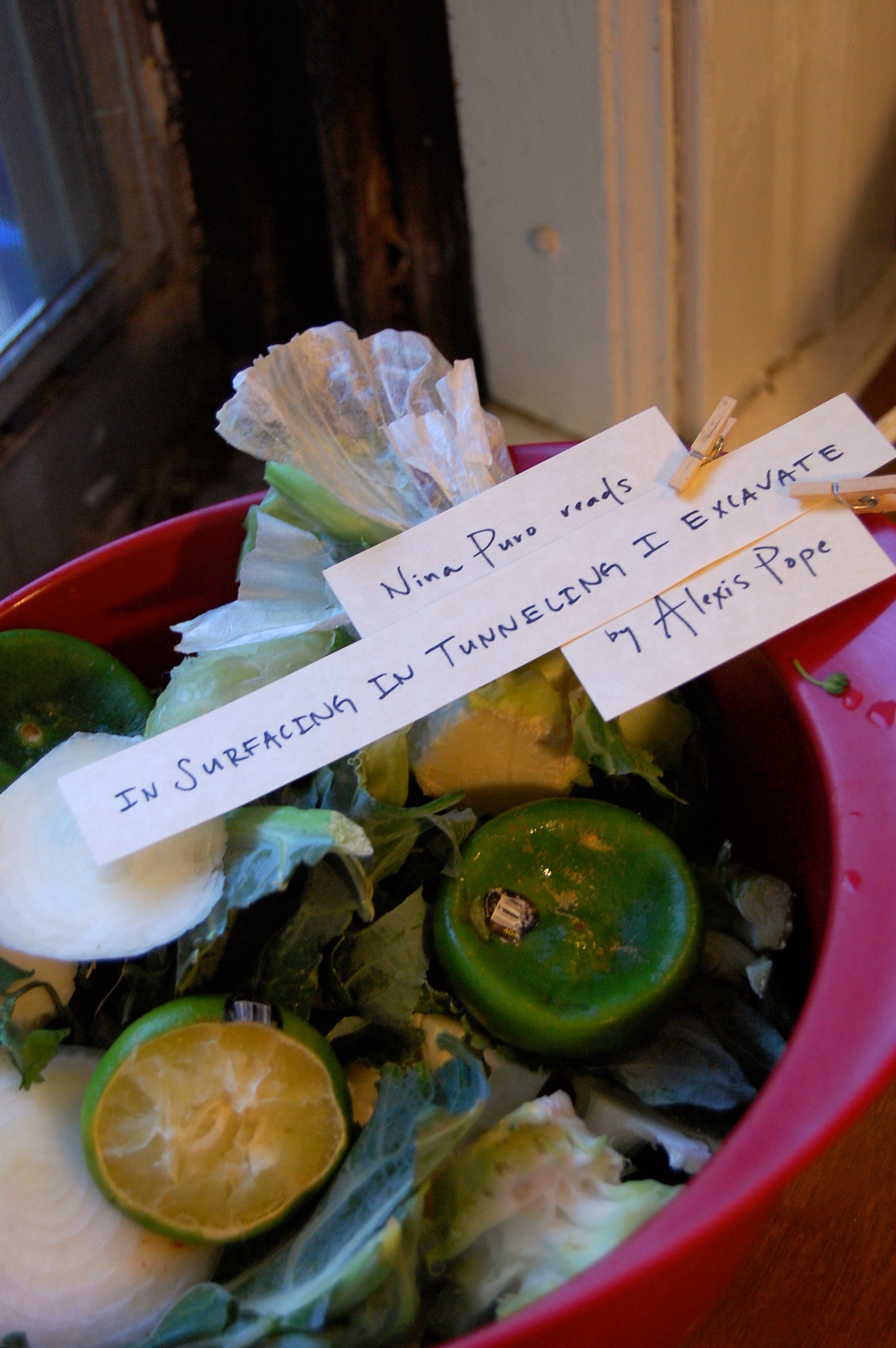

Much of what I love about “In Surfacing In Tunneling I Excavate” is related to the emotional registers the poem plaits together, both in terms of appearance on the page and tonal valences.

The poem catalogues remembered trauma, grief, motherhood within the fractured lineage of women, the end of a relationship, and building a home and a life despite these obstacles.

I built// a tunnel through the wilderness I built a new/

window to close for you I used my real hands

As Alexis reads, she rocks back and forth. I didn’t understand this until I saw her read with her daughter, Willa. I don’t know that she understood why she rocks until she read with her daughter. Perhaps that’s not why, but regardless, Alexis is a nurturer.

In this poem, her rocking its not clearly embedded via linebreaks as overtly as in much of her other work, yet I can hear her voice swaying under them. By which I mean that, comparatively speaking, the tide in this poem is an undercurrent, but it is steady and strong and assuredly hers.

The poem is suffused with anger and reckoning, the threads between past and present fraying and being restitched; the fragility of bodies and the terror of responsibility for keeping another person’s body safe: “the first time I saw her/ blood there was fire/ in me I was on fire.” About autonomy and depersonalization within mothering, the “violence in this love.”

The poem also addresses building a home within language and the tradition of writing, imperialist as it is. Her work is suffused with the marks of those that changed her in a way that seeks to honor, rather than name-drop.

On that note, while neither she nor I had a damn to do with my being asked to write this, Alexis is a personal friend of not a particularly long duration but remarkable closeness. (By which I mean much mutual sobbing.)

Alexis Pope is a door. She is someone who showed me what it is to be let in, what to close out. She taught me what is to be part of a rhizomatic chain of connections. She taught me things I didn’t know I didn’t know about mothering myself and others.

“I put it in my desk drawer” “I thought about healing” “thought about my women” “my friends” “about the shells” “if they released them” “back to the sea” “what does that mean” “for the rest of us”

This poem is rupture and suture, gloss and spit. This poem is a container that opens and opens, an apparatus tunneling deeper, a room.

I don’t want to make this all about our personal relationship, but: I am sitting trying to write this thing but am too damn depressed for language and she texts me telling me she’s sad.

Alexis’ room has room for the inexpressible: for the unsayable, scattered stutters and gaps.

what little I can mend it happened

again the glistening

(where does language fail me)

This room honors the everyday and lived experience in a deeply feminist manner.

cute as fuck

he looked me in the eyes while

he passed me on

the street my black skirt

my white keds

***

I half-want to ask her who the poem is about. It is angry; it is about wanting to shut someone out; and I am always afraid I am imposing. I suspect this is paranoia; knowing this, e.g. suppressing the impulse to indulge my anxiety by asking someone else an annoying question when they are probably bathing their daughter, is part of what Alexis teaches me.

She teaches me how to be fully present for another person when they are in the room; how to leave them alone so that they can cry and mother and work.

She teaches me, too, about another kind of not-knowing, something that’s a close relative of negative capability, but not quite akin to it: to suppress my niggling urge to know, to have the poem be explainable. She’s taught me to trust myself to read and write work that sways toward the experimental without feeling idiotic. To learn what I was mis-taught and teach myself better.

(I remember) (learning) (how to tie) (my shoe but) (I wanted to pretend) (I couldn’t)

(the teachers) (were passing out) (special attachments) (the song about) (a bunny)

(I felt) (left out so I) (pretended) (I knew less) (than I did)

(what forms) (do I) (forget) (in order) (to be) (included)

(blend in) (she tells you) (you don’t want) (them to) (notice)

I took Alexis and her daughter Willa to Willa’s first poetry reading, at which she and I both read. It was a bright February afternoon, slushy from heavy snowfall the night before. It took us 45 minutes to get 20 blocks. Every moment of that walk felt like an essay.

The work of two women on a Sunday in Brooklyn pushing a stroller. Willa walking and wanting to be pushed; Willa being pushed and wanting to be carried; convincing Willa to be pushed just until the end of the block. Puddles at every curb, one of us lifting the stroller and one Willa, both lifting the stroller together with Willa in it, Willa skipping across the puddles.

Men informing us that Willa’s shoes were untied or hat was on or off; questions about our day that were implicit demands for a response. The complication that these men were mostly black men and we were two white women with good coats in a historically black neighborhood. The casual violence of gentrification, the plea embedded in the male gaze.

The press of economy, of time, the traditional workweek inching closer. The eyes of brunchers languidly asking if we were a couple. Willa getting hungry, a stop in a fancy café on a hulking pretty on a corner of a block spattered with crappy Chinese food, bodegas, a nail salon. Everyone inside white and laptopped. A croissant. The addition of a blood orange San Pellegrino soda, whose label Willa recognized as her favorite juice from the back of the café, her whispering it to her mother because she is afraid to speak aloud around strangers. The reading starting, five more blocks, my arms aching. I had forgotten the degree of difficulty involved in getting a small person 20 blocks, and Alexis cannot forget. Childlessness as a form of privilege.

I’m a cynical, introverted non-breeder/ mad aunt who doesn’t always like children, but I have been marked by the privilege of going to Willa’s second and third readings, of watching her unfold. I feel lucky.

I feel lucky this scrappy, attentive poem unfolding is in the world, in all its tenuous ferocity and devotion.

Nina Puro’s work can be found in Guernica, H_ngm_n, the PENPoetry Series, and other places. She is a member of the Belladonna* Collaborative and the author of two forthcoming chapbooks (Argos Books and dancing girl press). She lives and cries in Brooklyn.