In his iconic “Wilderness Letter,” Wallace Stegner asserts that “we need wilderness preserved…because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed.”

For many, Stegner remains the great myth-maker of the American West, stitching epics from public chronicles and family lore, from sagebrush and big sky. His formulation of the American “character” is a kind of poetic precipitate, the side-effect of crossing imagination with landscape. If wild places disappear, Stegner warns:

[N]ever again can we have the chance to see ourselves single, separate, vertical and individual in the world, part of the environment of trees and rocks and soil, brother to the other animals, part of the natural world and competent to belong in it.

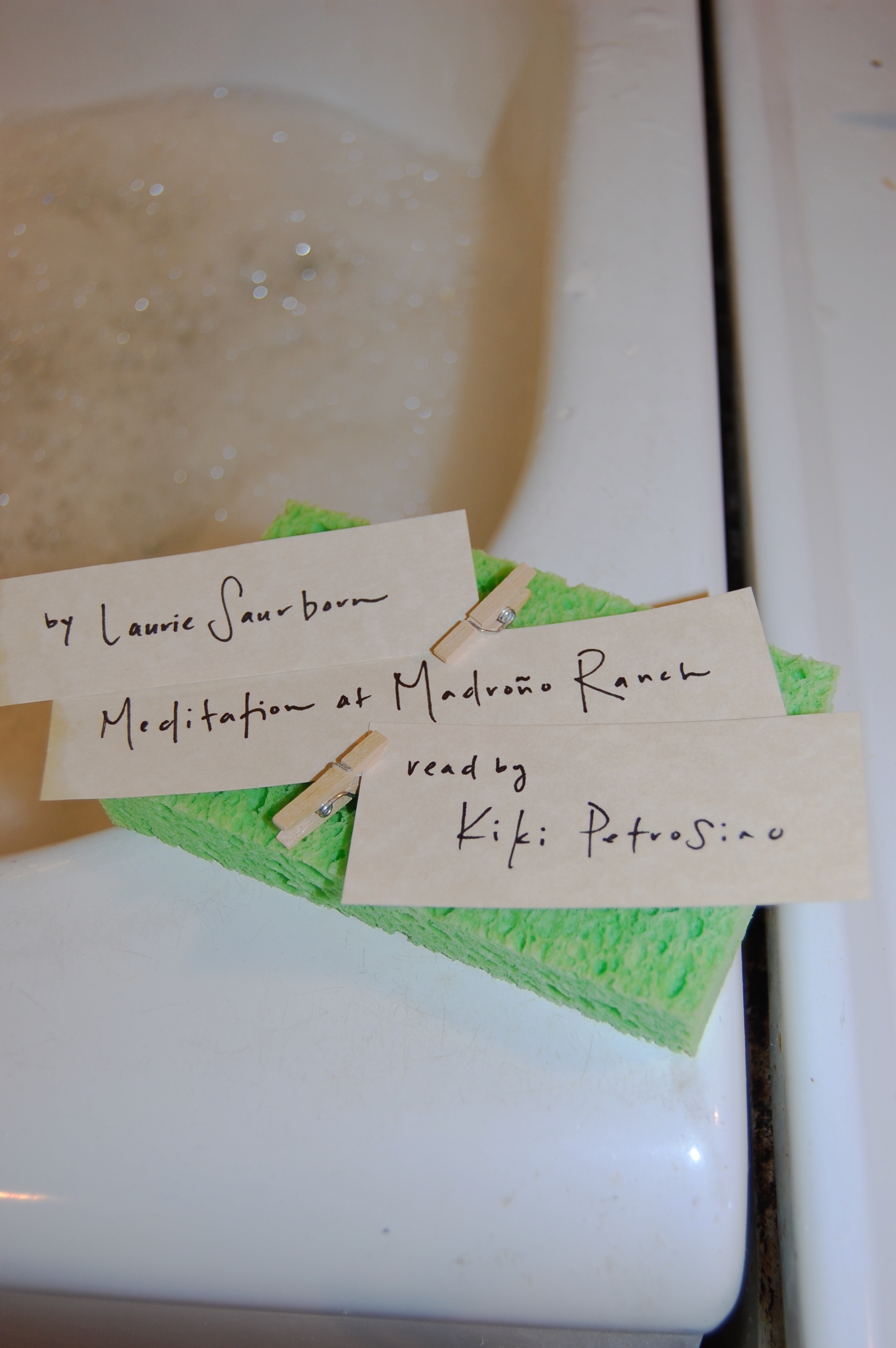

Of course, Stegner has a decidedly male, heteronormative way of talking about American “competencies.” Laurie Saurborn's poetry shows us other directions beyond the vertical, and more kinds of bodies than those of “brothers.” Her poem, “Meditation at Madroño Ranch,” purposefully collides the wild with the domestic in couplets that meld these seemingly disparate topographies. The language that comes from this procedure is rich, deeply inhabited, and energetically connected to the “wilderness” of the page, never “vertical,” or “separate” from the world(s) it contemplates.

Take the working ranch which is the primary setting for this poem. It’s an acreage, yes. It’s Texan, measurable, as boundaried as the couplets which govern the poem itself. The speaker describes windows, screens, kitchens, kettles: all markers signifying home-like interiors and settled spaces. Even the “thin hunting dog” that appears outside the window has a job, a purpose, belongs to someone. At the same time, Saurborn's Madroño is a wild nexus, admitting brief glimpses of mystery:

In the dark, a howl

I think it is the wind

but the wind keeps moving

and I never hear the call again

Initially, Saurborn's I stays close to her cabin, her kitchen sink and its circling ants, the patio with its “moldy cushions.” Her observations of the landscape outside her window draw us back to the trappings of womanly domesticity: “Clouds spread out, slow/milk in the sky.” Her realization that “[a] whole life may be wasted/perfecting the argument” is buttressed, on one side, with an isolated artifact from the natural world (the small fossil known as a “deer’s heart”) and, on the other, with a memory artifact from her time-before-the-ranch: “as when the hairdresser/asks after my kids/and I don’t bother to correct her.”

As with Stegner’s re-imagining of the American “character,” Saurborn's speaker arrives at wisdom by confronting a perplexing challenge from nature (i.e., the deer’s heart, a fossil whose pleasing shape is incidental to its creation, but which nevertheless attains a perfect beauty). But, in equal measure, this speaker also interrogates her connection to the social landscape outside Madroño, i.e., the terrain of her everyday life, which is marked, problematically, by externally-imposed definitions of class and gender roles. Between nature’s profound, yet inexplicable perfection and the crafted, intentional world of “hairdressers” is the speaker’s “whole life,” an “argument” which must be lived out rather than “wasted” through endless second-guessing.

Later in the poem, the speaker contemplates the stars:

Pin light, puncture. Rend and rupture.

Stay in place for years enough,

Myth starts breaking down.

Wearing a bison hide as mythic token, the speaker now immerses herself in a charged landscape of geographical and emotional vastness. She fully inhabits this wilderness, a place where stars and myth cannot map the way (note that it’s “dusk” in the poem here, a time of blurred boundaries). We are now far from cabins and kettles, with the speaker guiding her own meditation. The intimacy the speaker enjoys with the Madroño landscape feels more intentional for the duration of the poem, chosen rather than merely observed. One of the poem’s final images exemplifies this condition of generative boundarilessness:

Exhaust drifts in the noon grass.

I wash my face but it does not cease

folding into itself, merging

solar and subterrain.

As we see, Saurborn's lyric meditation refreshes our definitions of seemingly fixed concepts. At Madroño, “drift[ing]” can generate new wisdom, and the act of “fold[ing]” may reveal an endlessly emerging self to the waiting world.

Kiki Petrosino is the author of two books of poetry: Hymn for the Black Terrific (2013) and Fort Red Border (2009), both from Sarabande Books. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and the University of Iowa Writer's Workshop. Her poems have appeared in Best American Poetry, The New York Times, FENCE, Gulf Coast, Jubilat, Tin House and elsewhere. She is founder and co-editor of Transom, an independent on-line poetry journal. She is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Louisville, where she directs the Creative Writing Program.